Apolipoprotein B (ApoB): What It Means for Your Cardiometabolic Risk

ApoB measures the number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles—like LDL, VLDL, and Lp(a)—that drive plaque formation. It’s a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than traditional cholesterol tests like LDL-cholesterol.

What Is ApoB?

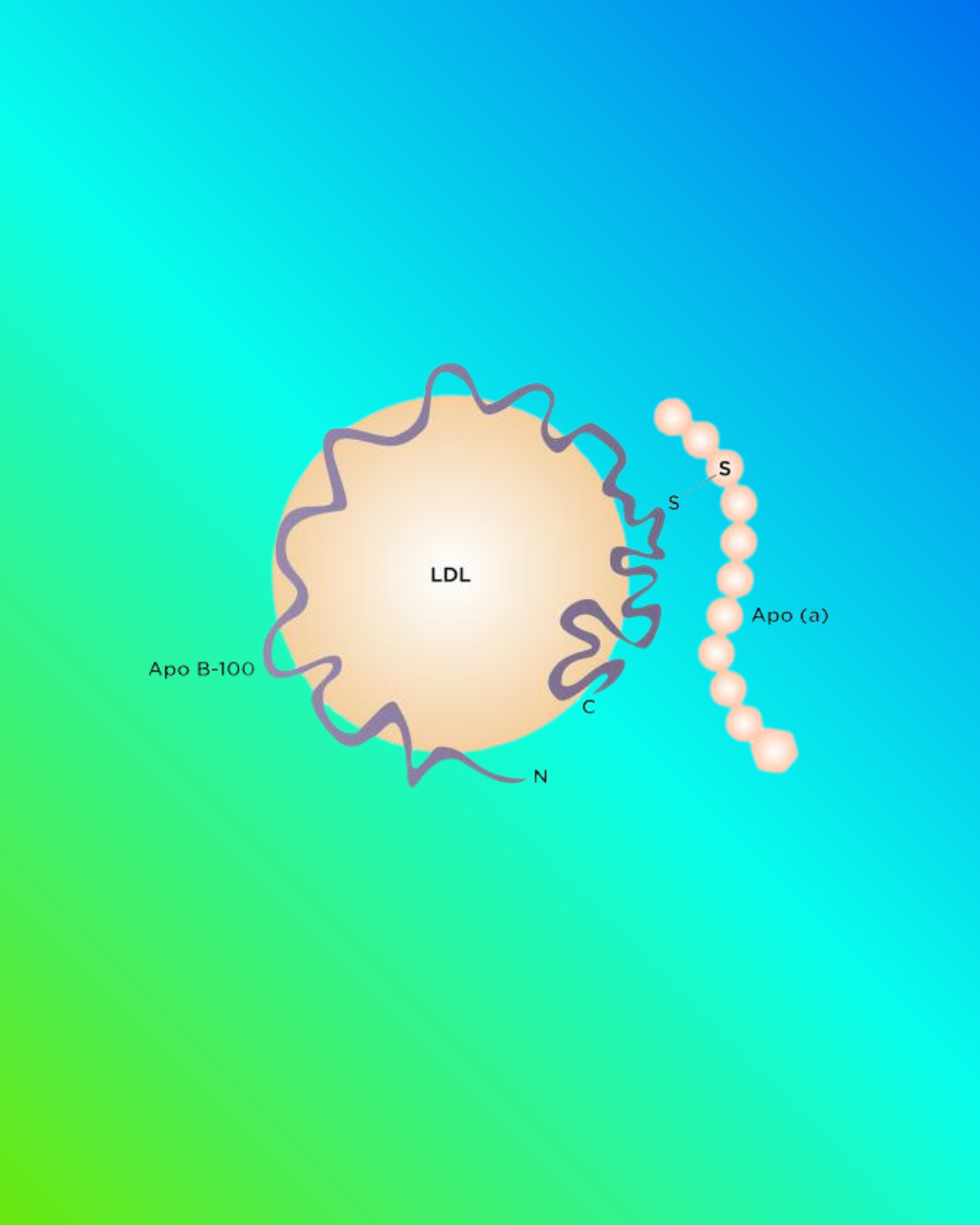

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is a protein found on the surface of all atherogenic lipoprotein particles: LDL, VLDL, IDL, and Lp(a). Because each one of these particles carries exactly one ApoB molecule, the ApoB test is effectively a count of the total number of particles that can enter artery walls and contribute to plaque formation.

ApoB is more than a cholesterol number. It measures the actual particle load that drives cardiovascular disease. This makes it a clearer, more stable indicator of risk, especially when cholesterol levels appear “normal,” but the number of particles is high.

Fast Facts

Full name: Apolipoprotein B-100

What it measures: Number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles

Sample type: Standard blood sample

Typical reporting units: mg/dL

Why it matters: High ApoB = higher particle burden = higher ASCVD risk

Commonly ordered with: Lipid panel, non-HDL-C, triglycerides, Lp(a)

Why ApoB Matters

ApoB provides a more precise view of cardiovascular risk because it reflects the number of artery-penetrating particles, not just how much cholesterol they carry.

Traditional cholesterol tests (like LDL-C) measure how much cholesterol is inside LDL particles, but people vary widely in how many particles they produce. Two people can have the same LDL-C level yet very different ApoB levels, leading to very different actual risks.

ApoB is especially valuable because it:

Predicts heart attack and stroke risk more accurately than LDL-C in many individuals

Identifies risk when triglycerides are elevated or metabolic syndrome is present

Detects discordance, where LDL-C looks normal but particle number is high

Reflects the risk contribution of Lp(a) and other remnant particles

Provides a stable, guideline-aligned metric for monitoring treatment response

Multiple international guidelines—including the ACC/AHA, NLA, ESC/EAS, CCS, and IAS—recognize ApoB as a risk-enhancing biomarker that refines cardiovascular risk, especially in individuals with high triglycerides, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or discordant LDL-C. These organizations endorse ApoB because it captures the total number of atherogenic particles that contribute to plaque formation.

✅ 2018 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol (USA)

Designation: Risk-enhancing factor

Relevance:

ApoB ≥130 mg/dL is listed as a risk-enhancing marker that supports statin therapy in borderline/intermediate-risk adults.

Used to refine risk when LDL-C does not fully reflect particle burden.

✅ 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guideline

Designation: Risk-enhancing biomarker

Relevance:

Reiterates ApoB as a factor that reclassifies ASCVD risk upward.

Helpful in metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and hypertriglyceridemia.

✅ National Lipid Association (NLA) Scientific Statement (2022)

Designation: Primary measure of atherogenic burden

Relevance:

Positions ApoB as superior to LDL-C and non-HDL-C when discordance exists.

Advocates for explicit ApoB-based treatment targets.

Strongest U.S. endorsement for ApoB use in clinical practice.

✅ Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) Guidelines (2016, updated 2021)

Designation: Preferred secondary metric

Relevance:

ApoB recommended as an alternative primary treatment target to LDL-C or non-HDL-C.

Particularly recommended when triglycerides are elevated.

✅ European Society of Cardiology / European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) Guidelines (2019)

Designation: Risk-refining biomarker

Relevance:

ApoB included as a secondary treatment target, especially useful when TGs are high or in metabolic syndrome.

Recognizes ApoB as a more accurate marker of atherogenic particles.

✅ International Atherosclerosis Society (IAS) Global Recommendations

Designation: Primary indicator of atherogenic lipoproteins

Relevance:

ApoB is recommended as the best single measure of circulating atherogenic particles.

Strong advocacy for global adoption of ApoB testing.

✅ ADA (American Diabetes Association) Standards of Care

Designation: Enhancer of cardiovascular risk understanding in diabetes

Relevance:

Recognizes the utility of ApoB in patients with diabetes or insulin resistance, where LDL-C can underestimate risk.

ApoB Interpretation: Typical Ranges

The typical risk ranges for ApoB vary across different guidelines.

| ApoB (mg/dL) | Typical Interpretation |

|---|---|

| < 60 | Very low target, often used for people with known cardiovascular disease or very high risk. |

| < 70 | Common treatment goal for high-risk individuals based on several expert consensus statements. |

| < 90 | Reasonable target for many people with borderline or intermediate ASCVD risk. |

| 90–129 | Elevated ApoB; may indicate increased atherogenic particle burden and higher ASCVD risk. |

| ≥ 130 | High ApoB and considered a risk-enhancing factor in several cardiovascular guidelines. |

These ranges are for educational purposes and may not match the exact reference intervals used by your lab. ApoB should always be interpreted in the context of your full clinical picture and guideline-based ASCVD risk assessment in consultation with a qualified clinician.

ApoB should always be interpreted in the context of:

age, gender/sex, ethnicity

other lipid markers (LDL-C, non-HDL-C)

metabolic syndrome features

blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes status

family history of premature cardiovascular disease

presence of plaque as indicated by noninvasive imaging

other chronic conditions such as autoimmune conditions, erectile dysfunction, or preeclampsia

When an ApoB Test Is Especially Useful

ApoB provides clarity in situations where traditional cholesterol numbers may not tell the full story. It is particularly helpful when:

Triglycerides are elevated (≥ 200 mg/dL)

Metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance is present

Type 2 diabetes is diagnosed or suspected

LDL-C appears normal, but risk is still uncertain

Non-HDL-C and LDL-C disagree (discordance)

There is a strong family history of premature heart disease

Lipoprotein(a) is elevated

Familial hypercholesterolemia is suspected or identified within other family members

For many people, ApoB is the difference between “normal cholesterol” and “elevated risk.”

ApoB vs LDL-C vs Non-HDL-C

LDL-C

Measures how much cholesterol is inside LDL particles.

Does not tell you how many particles there are.

Non-HDL-C

Includes LDL-C plus VLDL and other remnant particles.

Better than LDL-C alone, but still based on cholesterol content, not particle count.

ApoB

Measures the number of atherogenic particles—what LDL-C and non-HDL-C are attempting to estimate.

Stronger predictor of plaque formation and cardiovascular events, especially when cholesterol values and particle numbers don’t align.

Factors That Raise or Lower ApoB

Factors that can raise ApoB

Diets high in saturated fat

Refined carbohydrates and sugar

Visceral adiposity and overweight

Metabolic syndrome

Type 2 diabetes or prediabetes

Hypertriglyceridemia

Familial hypercholesterolemia

Chronic kidney disease

Elevated Lp(a)

Factors that can lower ApoB

Statins

Ezetimibe

PCSK9 inhibitors

Weight loss

Improved diet quality (fiber-rich, lower saturated fat)

Increased physical activity

Better glycemic control in diabetes

Smoking cessation

What To Do If Your ApoB Is High

If your ApoB level is above the ideal range, consider discussing the following with your clinician:

Confirm your overall cardiovascular risk.

This includes your age, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, diabetes status, family history, ethnicity, and lifestyle factors.

Review lifestyle strategies.

Improvements in diet, physical activity, sleep, stress management, and weight can meaningfully lower particle numbers.

Discuss medication options if appropriate.

Statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and other therapies can lower ApoB safely and effectively.

Evaluate other risk-enhancing markers.

Triglycerides, Lp(a), GlycA, LP-IR, or metabolic syndrome severity may help refine risk.

Consider a comprehensive cardiometabolic risk analysis.

Precision Health Reports integrates ApoB with guideline-based risk calculators and additional biomarkers to show your personalized cardiometabolic risk and most effective next steps.

How Precision Health Reports Uses ApoB

ApoB is a core component of the Cardiometabolic Risk Assessment (CMRA). Our assessments:

Combine ApoB with LDL-C, non-HDL-C, triglycerides, HDL-C, and Lp(a)

Evaluate particle-based risk and cholesterol-based risk together

Identify discordance patterns that standard panels miss

Integrate metabolic syndrome severity, insulin resistance, and inflammation markers

Use guideline-aligned risk calculators (PREVENT, PCE)

Provide personalized recommendations based on your unique risk profile

ApoB isn’t just a number—it’s part of a broader, personalized picture of your cardiometabolic health.

FAQs about ApoB

-

Almost always, the answer is, yes. ApoB is a direct measure of particle number and predicts cardiovascular risk more accurately, especially in metabolic syndrome or diabetes. LDL-C can miss risk in people who are discordant.

-

Typically at baseline and then periodically to monitor risk or treatment response. Your clinician can guide timing. Depending on individual risk and current interventions, this could be as frequently as about every 3 months or as long as a year.

-

Yes. This is called discordance, and it can identify hidden cardiovascular risk.

-

Both. Family history can influence particle production, but lifestyle and treatment can significantly modify ApoB levels.

Additional References: ApoB

American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)

Grundy SM, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(24):e285–e350.

https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2018/11/08/14/24/2018-guideline-on-the-management-of-blood-cholesterol

Arnett DK, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596–e646.

https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2019/03/07/16/00/2019-acc-aha-guideline-on-primary-prevention-gl-prevention

National Lipid Association (NLA)

Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Role of Apolipoprotein B in Clinical Management of Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: NLA Scientific Statement. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2022;16(4):e85–e120.

https://www.lipid.org/nla/role-apolipoprotein-b-clinical-management-cardiovascular-risk-adults-expert-clinical-consensus

European Society of Cardiology / European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS)

Mach F, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. European Heart Journal. 2020;41(1):111–188.

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Dyslipidaemias-Management-of

Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS)

Anderson TJ, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Dyslipidemia. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2016;32(11):1263–1282.

https://www.onlinecjc.ca/article/S0828-282X(16)30732-2/fulltext

(2021 Practice Update summary available here:)

https://www.onlinecjc.ca/article/S0828-282X(20)31052-3/fulltext

International Atherosclerosis Society (IAS)

Sniderman AD, et al. Apolipoprotein B Particles and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: IAS Position Statement. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2019;13(5):669–683.

https://www.lipidjournal.com/article/S1933-2874(19)30265-X/fulltext

American Diabetes Association (ADA)

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2024: Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S190–S206.

https://diabetesjournals.org/care/issue/47/Supplement_1

Key Peer-Reviewed Research Supporting ApoB

Sniderman AD, et al. Apolipoprotein B Versus Non–HDL Cholesterol and LDL Cholesterol as a Cardiovascular Risk Marker. Lancet. 2003;361:777–780.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673603127221

Pencina MJ, et al. Discordance Between LDL-C and ApoB and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2015;132(13):1204–1211.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015669

Ference BA, et al. Low-Density Lipoproteins Cause Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: 1st of 2 Part Series.European Heart Journal. 2017;38(32):2459–2472.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/38/32/2459/3745109

Johannesen CDL, et al. ApoB and Risk of Myocardial Infarction in the General Population. Clinical Chemistry. 2020;66(5):706–716.

https://academic.oup.com/clinchem/article/66/5/706/5680971

ASCVD Risk & ApoB Utility

Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Use of ApoB as a Marker of Atherogenic Lipoprotein Burden in Guidelines and Prevention.Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;75(6):550–562.

https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.030

Toth PP, et al. Practical Application of ApoB in Clinical Decision-Making. Atherosclerosis. 2019;282:85–93.

https://www.atherosclerosis-journal.com/article/S0021-9150(19)30157-0/fulltext